When you head to your favourite online travel agent’s website and search for flights, you get back hundreds or even thousands of results in a matter of seconds. But have you ever wondered how that happens?

In our new "Inside the Cockpit" series here on the Duffel blog, we'll take you behind the scenes of the travel industry so you can see how it really works.

In this post, you'll learn what has to happen to bring you your flight search results at lightning speed.

Setting the scene

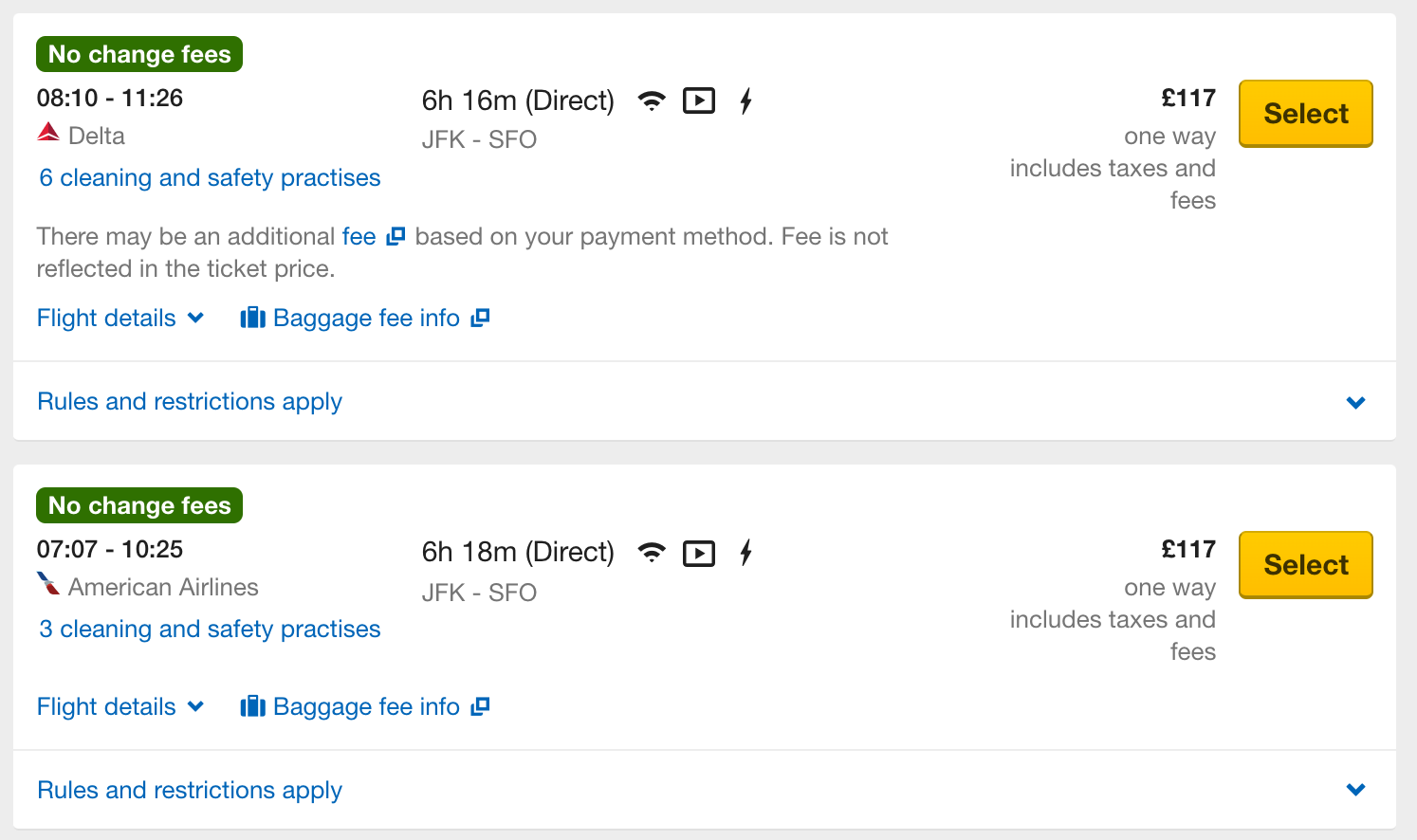

Imagine that you search for flights from New York John F Kennedy (JFK) to San Francisco (SFO) on 29th August.

To find your flights, the search engine (sometimes called a “pricing engine” or “shopping engine”) has to cleverly combine together three kinds of data:

- Schedules

- Fares

- Availability

Let’s look at these, one by one, to understand what they are and how they work. We’ll then talk about the hard part: combining them together to build the search results you see on your screen

Schedules

Schedules describe when and where an airline plans to fly.

This isn’t just a list of individual flights. Schedules are structured with a start date and an end date, and then the days of the week when the flight is set to operate.

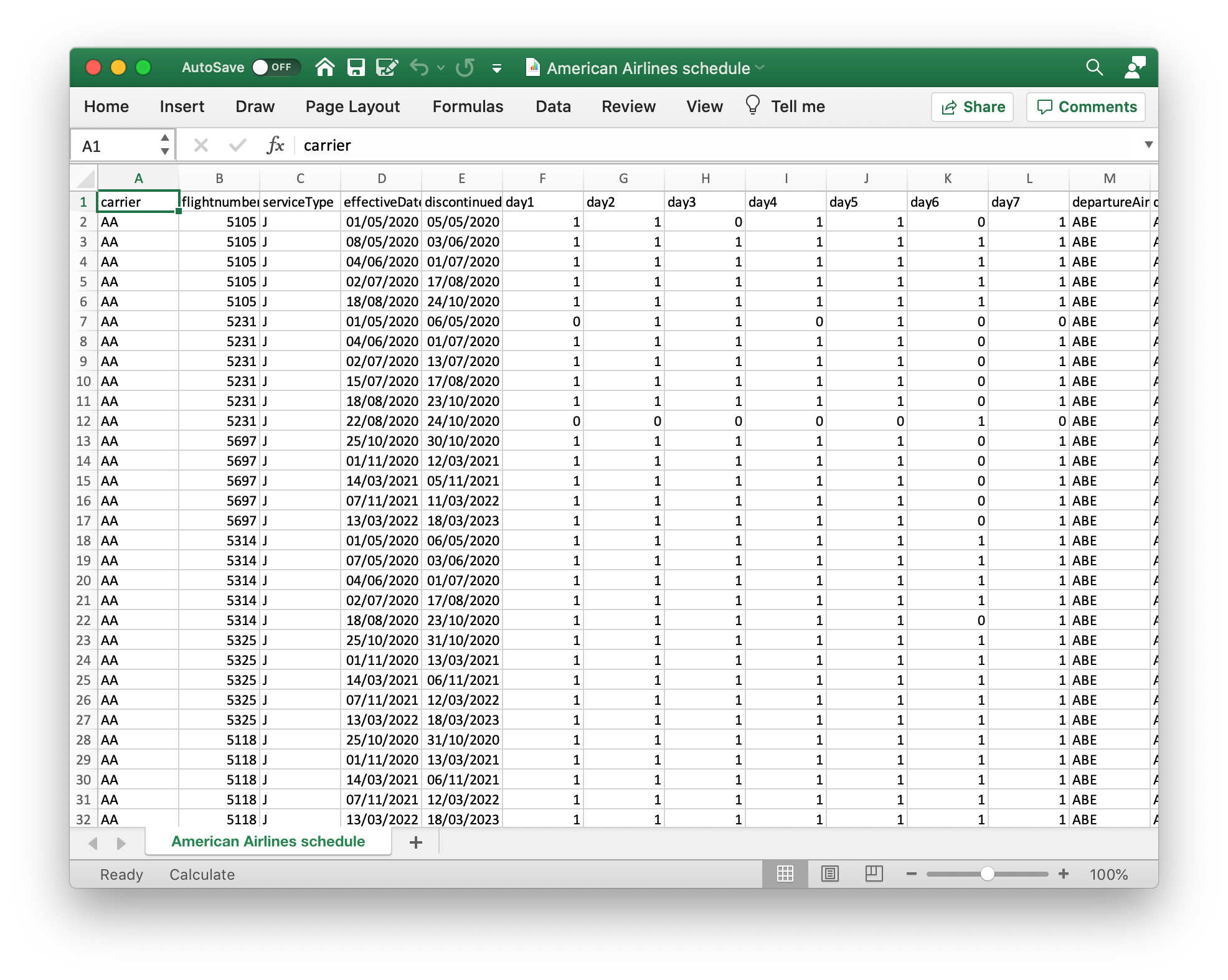

For example, an entry in American Airlines’ schedules might say something like this:

We’re going to run a flight from JFK to SFO on Mondays, Fridays and Sundays between 1st August and 31st August 2020. We’ll call this flight AA2305, and we’ll use an Airbus A321 to operate it.

Airlines distribute their schedules through industry data providers, who then make them available to other airlines, travel sellers and tech providers. OAG and Cirium are the leaders in this space.

This isn’t just static data which changes infrequently - airlines generally update their schedules at least once a day, and there are about 800 scheduled airlines for the data providers to work with.

Fares

A fare describes a price at which an airline is willing to sell seats on a particular flight, and the rules (sometimes known as "conditions") that go with that price.

A fare from American Airlines might look something like this:

We’re willing to sell seats on our flights AA2305 and AA2307 for $200, as long as there is space in booking class N. However, you must book your seat as part of a return, you’ll have to stay in San Francisco for a Saturday night, and we won’t give you any refund if you want to cancel.

A fare has a name, called a “fare basis code”. A fare basis code is a short set of letters and numbers - for example NVAKZNM3.

Fares are made up of rules which describe who is eligible for them, what flights they can be used for, and restrictions on how they can be sold or used. Examples of fare rules could include:

- You must fly via Los Angeles (

LAX) - You can change flights, but only if you pay a $50 penalty

- You can't have a "stopover" overnight on your journey

The full fare rules for a fare can easily be thousands of words long - you can see the real-life fare rules for the American Airlines fare NVAKZNM3 here.

Fortunately, the most important fare rules can be described in a structured way which a computer can understand, allowing a search engine to work out what fares match your search without a human reading through manually.

Airlines file their fares in an industry directory run by ATPCO, which other airlines, travel sellers and tech providers can subscribe to. Each airline can change their pricing by refiling fares many times a day. All in all, ATPCO processes more than 10 million fare updates per day.

Airlines offer many fares for the same flight at the same time, since a traveller won’t always want the cheapest, most restrictive option. For example, you might want a checked bag, or the ability to change your flights free of charge.

Availability

Airlines don’t just say “this flight has seats available” or “this flight doesn’t have seats available”.

Airlines want to make as much money as they can from their metal boxes flying through the sky, so they want to sell some seats cheaply, but hold some seats back for travellers who are willing to pay more.

A flight is broken into different “booking classes”, sometimes known as “reservation booking designators” (RBDs). These are letters of the alphabet, so a flight can be split into 26 different buckets: A, B, C, etc..

A fare points to a specific booking class. The example fare we looked at above, NVAKZNM3, is for the booking class N. Usually, the first character of the fare basis code is the booking class.

Each booking class on a flight can have different availability. For example, imagine that American Airlines uses the booking classes N, V and Y for economy.

They might use N for the most restrictive economy fares, Y for the most flexible ones and V for ones in the middle. Being able to control availability for each booking class means that “cheap economy” can be sold out, but there can still be “expensive economy” seats left.

Airlines don’t “publish” their availability. To know the latest, up-to-the-minute availability, you have to go to the airline’s passenger service system (PSS). Popular passenger service systems include Amadeus Altéa, Sabre Sonic and Navitaire New Skies.

Putting this all together

To find results for a simple search, a flight search engine has to combine together schedules, fares and availability.

There is only a small number of flight searches engines on the market. Most travel sellers use the search built into the global distribution system (GDS) they use (for example Amadeus, Sabre or Travelport). But there are competitors: airlines and larger sellers often use search solutions from providers like ITA Software by Google and PROS.

Flight search is very complex, and it requires a lot of computer power.

The first step is to identify possible routings. For our trip from New York to San Francisco, there are tens of thousands of reasonable options if we take into account connecting flights and the full range of available airlines.

At the simple end, we could take a direct flight, AA2305. But we could also fly with Alaska Airlines on AS17, AS398 and AS3311, connecting in Seattle (SEA) and Los Angeles (LAX).

For each of those routings, the search engine needs to work out what fares are applicable, checking all of the rules.

There can be hundreds or thousands of potentially relevant fares to check per airline, especially given that there can be many different ways to apply fares to a set of flights.

If we take our example above with Alaska Airlines, you’d fly from JFK-SEA, then SEA-LAX and finally LAX-SFO. In terms of fares, this could be structured as:

- A one-way from

JFK-SFO - A one-way from

JFK-SEA, and then a one-way fromSEA-SFO - Three one-ways:

JFK-SEA,SEA-LAXLAX-SFO - …

If we’re booking a round trip, this gets even more complex.

Once you’ve combined the schedules and fares, you’ll have a series of “priced itineraries” - for example:

You can fly on AA2305 direct from JFK to SFO for $200, using fare NVAKZNM3, as long as booking class N is available

The final step is to bring availability into the picture. You’ll probably find that a lot of your priced itineraries are not available because one or more of the booking classes you need are full.

The end result is a series of search results — or what we call "offers" in the Duffel API.

Wrapping up

When you search for flights, a flight search engine has to combine schedules, fares and availability to generate your search results.

To do this, it has to consider hundreds of millions of options (at least!), turning them into a relatively small number of valid, relevant combinations. And all of that in just a couple of seconds!

Latest posts

Traveltek Announces Duffel Integration Into iSell Platform

We are thrilled to announce that, Traveltek, a global leader in travel technology, just launched the latest upgrade to its award winning iSell Platform with the integration of Duffel.

Behind the Scenes: How Hotel Booking Works

Ever wondered what happens when you click the "Book Now" button for your next hotel stay? Dive into our latest blog post where we uncover the technology, strategy, and major players behind the scenes of hotel booking.

The Dynamic Duo: Why Travel and Spend Management are Inseparable

Check out this insightful article on the inseparable relationship between travel and spend management.

Traveltek Announces Duffel Integration Into iSell Platform

We are thrilled to announce that, Traveltek, a global leader in travel technology, just launched the latest upgrade to its award winning iSell Platform with the integration of Duffel.

Travel Industry

Behind the Scenes: How Hotel Booking Works

Ever wondered what happens when you click the "Book Now" button for your next hotel stay? Dive into our latest blog post where we uncover the technology, strategy, and major players behind the scenes of hotel booking.

The Dynamic Duo: Why Travel and Spend Management are Inseparable

Check out this insightful article on the inseparable relationship between travel and spend management.