You've landed on your favourite online travel agent's website, spent hours picking the right flights for you and taken the plunge and made a booking.

A few minutes later, you receive your booking reference via email which you can use to load up the booking on the airline's website. Have you ever wondered how that happens?

We kicked off our "Inside the Cockpit" series back in August by explaining what happens when you search for flights. Now, we're ready for the next step: the booking process.

Fasten your seatbelts and you'll learn how it works! We'll pretend we're the travel agent and go through the steps they follow to make a booking.

Flight search: a quick recap

Let's start with a quick recap of how flight search works. You'll need to understand this part of the process to get to grips with booking a flight.

When you search for flights, the search engine (sometimes called a "pricing engine" or a "shopping engine") has to cleverly combine together schedules, fares and availability to return your search results.

The search engine considers hundreds of millions of options and identifies a small number of relevant search results. It does all of that hard work in just a couple of seconds.

When you pick a search result that you want to book, you're effectively selecting:

- an itinerary — that is, a series of flights that get you where you want to go. Each of those flights is known as a "segment".

- a fare — that is, a price for those flights with a certain set of rules (sometimes known as "conditions") attached.

If you want to go over these bits in my detail, check out our "What happens when I search for flights?" explainer.

Creating a booking

When booking flights, the first step is to create a booking in the airline's system. In travel industry jargon, this is known as a "passenger name record" - or a PNR for short.

A booking will be created whether you book directly with the airline or through a travel agent. If you book through the latter, they'll be using a global distribution system (GDS) or a flights API like Duffel to talk to the airline's system.

The booking contains two key things:

- passengers: the first name, surname and title of the passenger(s)

- segments: the flights that the passenger(s) will fly on to complete their itinerary, plus the "booking class" that should be used for each one

You'll notice that no money changes hands at this point. We're just adding them to our "shopping basket" and asking the airline to reserve space on the segments for our passengers.

Getting back a booking reference

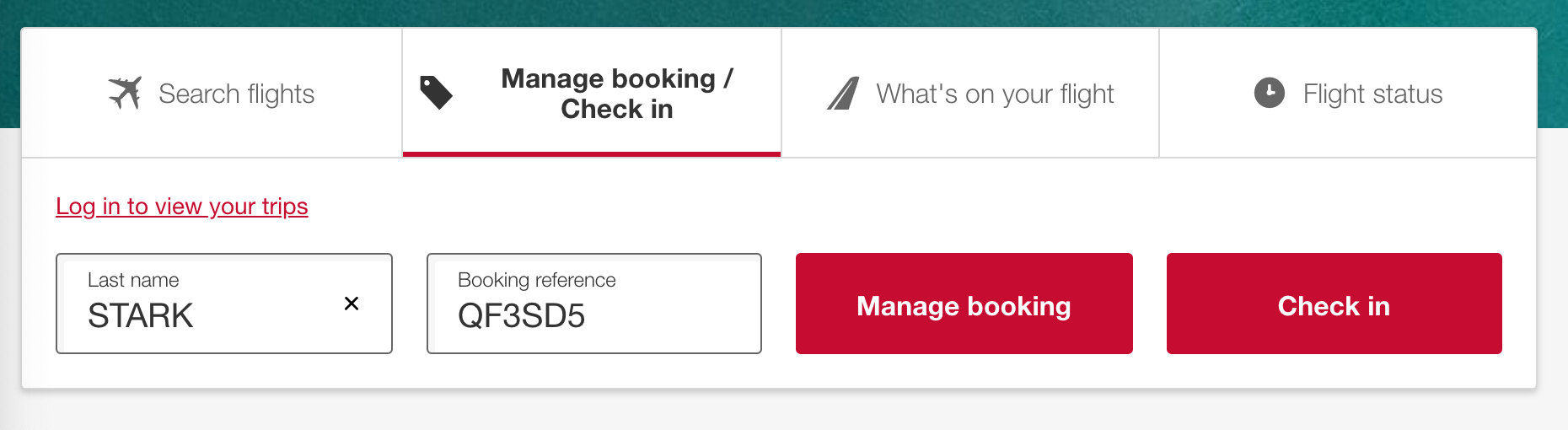

Once the PNR is saved in the airline's reservation system, we get back a booking reference (sometimes called a "record locator" or, confusingly, a PNR).

This series of random characters (for example QF3SD5) is used to access the booking on the airline's website. (Given that there is only a small number of possible booking references, you'll also have to provide a passenger's surname as a kind of password.)

One booking can have multiple booking references:

- If the booking is made through a GDS like Amadeus or Sabre, there can be a GDS booking reference and a separate one in the airline's reservation system.

- If the flight involves multiple airlines, then there can be a separate booking reference for each carrier involved.

Checking that the passengers' segments are confirmed

When we create our booking, we're having a kind of conversation with the airline's system. We ask the airline to reserve a space on segments the passengers want to fly on.

We ask, and we have to wait a response. We have to make sure that the airline's reservation system actually confirms the space before we move forward.

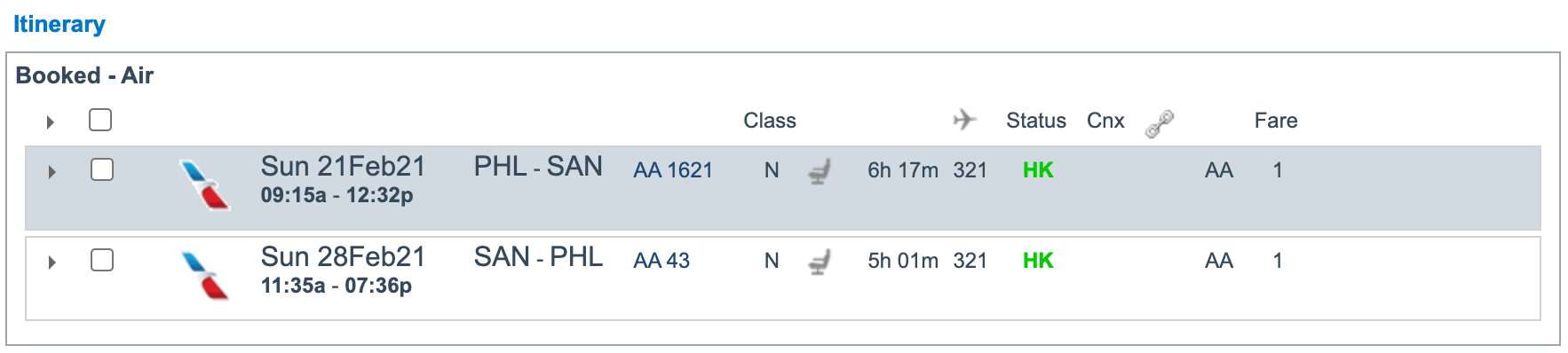

Each segment has a status which represents whether the passengers are "booked in". We want to see the status change to HK ("holding confirmed"), which means that the passengers' space on the flight is held.

Sometimes, this can go wrong and the airline replies with a stern "no" - for example, it could be that the booking class sold out between the search and when we tried to create the booking, leaving the passenger with no reservation and the unfortunate status code NO.

The magic codes here are defined by IATA's Passenger and Airport Data Interchange Standards - or PADIS for short.

Requesting additional services

Flight segments aren't the only "service" that we might want as part of our booking.

If we look across the passenger journey, there are all sorts of other "services" we might want, from extra help for passengers with disabilities to a pet in the cabin.

These are modelled in an airline's system using Special Service Requests (SSRs). An SSR is made up of a four-letter code, plus some structured or unstructured extra information to further describe the special service.

Just like when you request a segment, requesting a SSR starts a conversation. We have to wait for the airline to confirm it.

Let's say that we specify the SSR VGML to ask for a vegan meal. With this request, some metadata is required: references to the segment and passenger that the meal request replies to.

The airline's system has to check that the vegan meal is available on the flight you've requested it on. Once you've added this Special Service Request, you have to wait for it to change status to HK to know for sure if the passenger is going to get this special meal.

FALC. (Photo by Luke Jones, licensed under the CC BY 2.0 license.)Other SSRs include:

WCOBif the passenger needs a wheelchair on the plane, provided by the airlineFQTVto provide a passenger's loyalty programme informationDOCSto share Advanced Passenger Information needed before the passenger can fly, like their date of birth and identity document details

Pricing the booking

The search result we've picked combines together an itinerary and a fare - in other words, it specifies what flights we'll be taking and how much we'll pay.

Once we've created the booking, as a final check, we need to re-price it.

This makes sure that the available fares haven't changed since we did our initial search, and takes into account additional context we have now that we didn't have before (for example the final number of passengers and the payment method we plan to use to pay).

This will set the final price that we'll pay for the flights. The price quote is stored on the booking. Our shopping basket is now ready to take to the checkout.

Issuing the tickets

When you book a flight through an online travel agent or on the airline's website, you usually just go through one single checkout flow. But under the hood, there are actually two distinct steps:

- Booking, which records the passenger information and holds the space on the flight(s). This is what we've done so far.

- Ticketing, which processes the payment, completes the contract and gives the passenger(s) the "right to fly"

When you create a booking, the space on the flights is held for a certain period of time. The airline communicates a "ticketing time limit", telling us how long the space will be held. If we don't pay, the airline will free up that space so that someone else can book it.

Before the passengers have the "right to fly" on the segments, the travel seller has to issue the passengers' tickets.

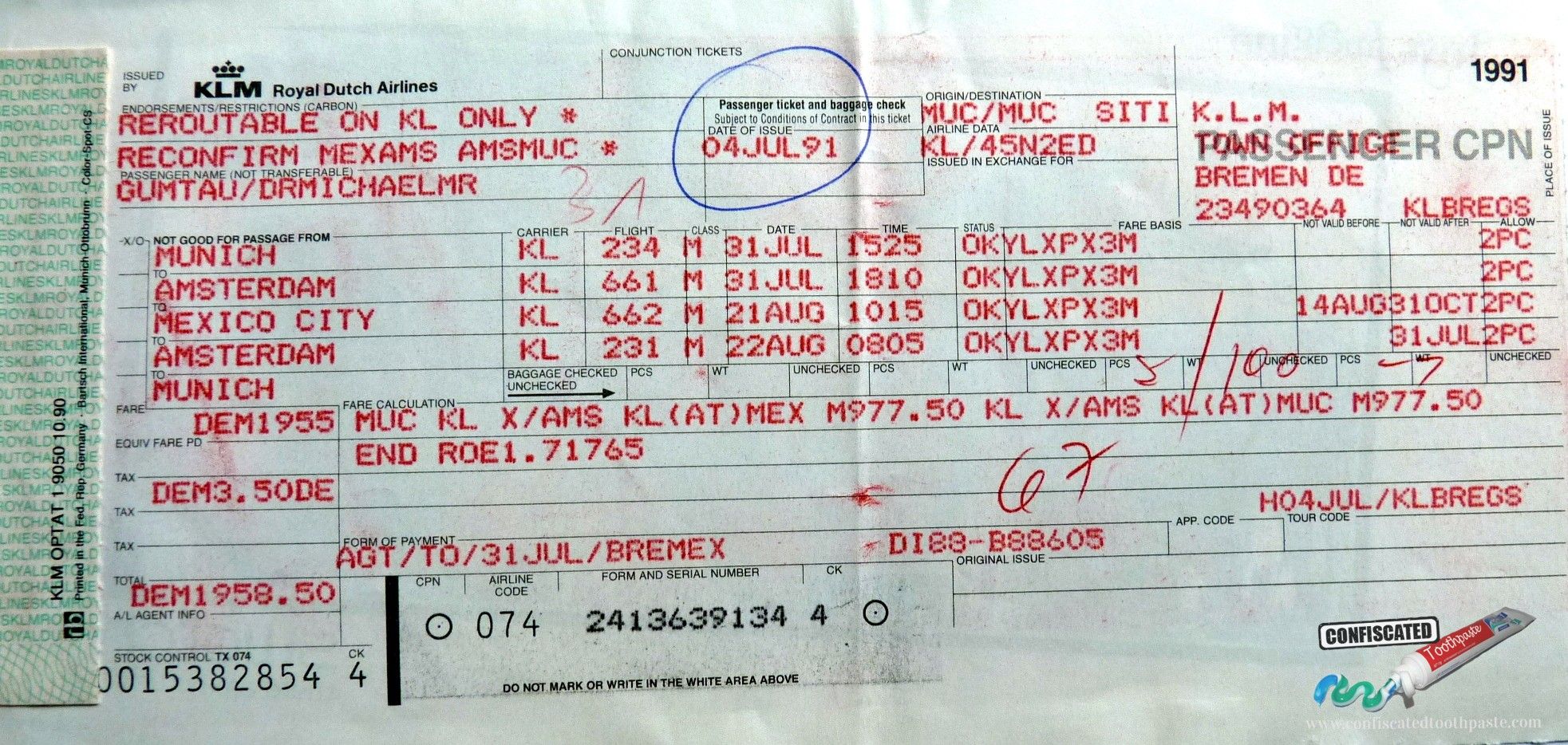

This harks back to the days before the internet where traditional travel agents had books of paper tickets which they wrote out and handed over to the passengers. Since the 2000s, these have been replaced with "electronic tickets" which only live in a computer system. But the terminology lives on.

When the tickets are issued, there is a "commitment to pay" and a contract is formed between the passengers and the airline.

The airline might charge a credit card belonging to the passenger or the agency. In many cases, the travel seller will use a special airline-specific payment method called "BSP cash" to pay.

Alongside the ticket, there is another kind of document called an electronic miscellaneous document (EMD) which is used to handle payments for the penalties charged when you change or refund your flights and paid extras like seats and bags.

Looking forward into the future

Airlines are working to modernise the booking process.

Some low cost carriers like easyJet or AirAsia already use a "ticketless" IT system. They still split "booking" from "commitment to pay", but they don't use the idea of a "ticket" which is based on the paper tickets of the past.

More traditional full service carriers like British Airways and Lufthansa are now heading in a similar direction. IATA's ONE Order initiative aims to replace "bookings" and "tickets" with "orders" and "payments". Each order will have a single standardised Order ID instead of multiple confusing booking references.

These changes aren't just about the customer experience - they're designed to streamline airlines' revenue accounting, make it easier for them to partner together and help them to offer products outside of the aviation ecosystem. Imagine, for example, if you could book an Uber inside your airline reservation!

Finishing up

In this post, we've taken you through the steps it takes for an online travel agent to book your flight when you check out on their website.

They create a booking, get back the booking reference, wait for the flights to be confirmed, add any special services, price the booking and then issue tickets. All of this happens in just seconds.

Latest posts

Traveltek Announces Duffel Integration Into iSell Platform

We are thrilled to announce that, Traveltek, a global leader in travel technology, just launched the latest upgrade to its award winning iSell Platform with the integration of Duffel.

Behind the Scenes: How Hotel Booking Works

Ever wondered what happens when you click the "Book Now" button for your next hotel stay? Dive into our latest blog post where we uncover the technology, strategy, and major players behind the scenes of hotel booking.

The Dynamic Duo: Why Travel and Spend Management are Inseparable

Check out this insightful article on the inseparable relationship between travel and spend management.

Traveltek Announces Duffel Integration Into iSell Platform

We are thrilled to announce that, Traveltek, a global leader in travel technology, just launched the latest upgrade to its award winning iSell Platform with the integration of Duffel.

Travel Industry

Behind the Scenes: How Hotel Booking Works

Ever wondered what happens when you click the "Book Now" button for your next hotel stay? Dive into our latest blog post where we uncover the technology, strategy, and major players behind the scenes of hotel booking.

The Dynamic Duo: Why Travel and Spend Management are Inseparable

Check out this insightful article on the inseparable relationship between travel and spend management.